On Photographic Sculpture:

A Conversation with Artist Stefanie Herr

I was in the last year of my university studies in 2001 at TU Berlin, when I had this particular aha moment that opened up the artistic universe for me. Back then, I was working with a fellow student and like-minded friend on our final project entitled «Snackscape». We were planning a service area along the European route E55, a north-south European highway that stretches between Helsingborg in Sweden to Kalamata in Greece.

I still remember my parents’ worried faces during the final public presentation. Rather than plans, sections and elevations, our presentation consisted of conceptual models, collages and a most memorable road movie (laughs). Among the exhibits was also a terrain model whose outer layer consisted of some 40 photo souvenirs we had brought home from our previous road trip, so as to illustrate the main ideas behind our project. It took me by surprise to see every single static image come alive and take over part of the territory. Another great thing about this model was that it had reflective coating on all except the upper side. As a result, the pictorial layer seemed to float above ground like a flying magic carpet. I knew right away I wanted to further explore the possibilities of both topographic and photographic sculpture.

There was a lady who approached us after the presentation, saying that the model belonged into an art gallery. Now imagine two enthusiastic soon-to-be architects. Of course, we did not take this seriously at all. In retrospect, however, the remark still haunts me to this day. In almost two and a half decades of artistic practice I have never heard these magic words come so easily again. Getting your work into a gallery can be challenging, if you lack a formal education in the visual arts and on top of that you are late starter. I have also realized that architects – as well as geographers – show a more nuanced understanding of my work. Interestingly, psychology tells us that people develop greater liking for the things they are familiar with.

You just don’t throw six grueling years of architecture school overboard from one day to another (laughs). After graduation I moved to Barcelona, a dream destination for any aspiring young architect back then. I have always enjoyed working with my hands and felt lucky to find a job in an office that was pushing the use of models as an important design tool. As a model maker within the team I was given plenty of room for creativity, which only fueled my artistic aspirations. Work was fun, but, as we live in a world that places excessive importance on production and economy, didn’t precisely allow for asking hard questions either. At some point – shortly before Spain’s epic housing bubble burst – I knew that my job had come to a dead end. I felt I had something more to say and to take responsibility for my personal beliefs and values, if I wanted to move forward. This is how photographic sculpture finally began to take shape.

Definitely! Life is way too short to not do the things in life that you are genuinely passionate about. Perhaps I should have planned a bit better (laughs). Self-employment comes with significant challenges, and failure is an intrinsic part of the journey. In spite of these setbacks, some lessons learned and others yet to come, I would not want my old routine back. I enjoy the freedom of working autonomously. Art is an invitation to stay curious – after all, it can be anything you want it to be and allows for speaking on topics and communicating ideas that are meaningful to you.

However, despite the Internet and social media, where instant fame seems to have become a new normal, I think it is still of great assistance to live in a place with a vibrant art scene and solid support for the arts and culture sector. Unfortunately, Barcelona and Spain are not among these places. This might sound a bit provocative to some, but it sometimes feels of not even being part of the art world over here. It’s hard to earn some decent money in Spain, even for non-artists. Yet I draw a much greater benefit from being able to make full use of my creativity than from the money I could possibly earn. Looking back at almost fifteen years of art making, I am satisfied with what I have achieved so far. I only wish I could have spent more time on producing artwork.

I guess my architectural education is to blame for the fact that the bi-dimensional plane has become a constraint for me. Architecture is all about physical space and its power precisely lies in going beyond two-dimensional presentations. These are too predictable (laughs). If I had gone to art school, I would have probably never come up with the idea of creating photographic sculpture. I find it fascinating to work with photography as sculpture, because it provides pictures you can literally walk into. Photography evolves in its desire to overcome its limits and seek out the unexpected. I also like how the simultaneity of the sculptural body with visuals from another context produces a sense of dislocation for which contemporary society provides the setting.

And yet, though I really try my best, I am aware that my photos do injustice to any real professional photographer out there. However, as I consider myself a conceptual artist, producing good pieces of photography is actually not the point of my artistic work. First and foremost, the photographic image serves to provide a layer of visual evidence for my thoughts.

This too shall pass. Artists have phases (laughs). But I have to admit that your question hits a sore spot, as it shows to what extent I am already questioning my original approach, photographic sculpture. The increasing role of the visual in the way we perceive our world today has its pitfalls. The overabundance of images not only causes fatigue, but also destroys our ability to imagine. At the same time, as paradoxical as that sounds, the power of images fades in a photo saturated world.

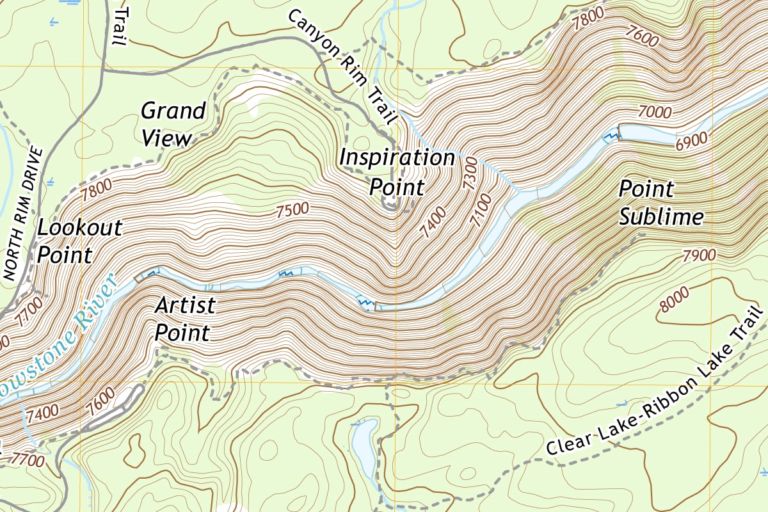

Well, first of all, maps allow us to travel somewhere else. However accurate they may be, they always remain simplifications, and as such enclose an infinite number of fictional worlds. I can easily lose myself in a map for hours, allowing the mind to float freely. I love the way geographical features, terrain shapes and place names evoke images, associations and metaphors. Topographic maps are particularly seductive, as contour lines not only convey depth, but also reinforce the idea of meandering.

It might be not so popular to talk about beauty these days, but it is also the aesthetic quality in cartography that draws me. For me, art is not a consumer product, but a vehicle of change. I feel that the visual arts are gaining particular momentum as a channel through which people look into environmental issues. As abstract representations of the landscape, maps perform an essential function in how we perceive and construct the world around us. I don’t think that scenic beauty is solely a matter of personal taste and hope to inspire a greater appreciation of landscape and environmental aesthetics through my work.

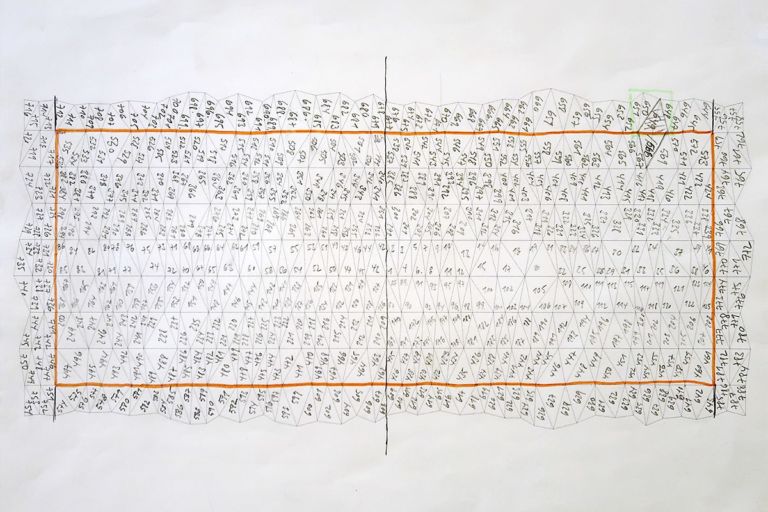

Believe it or not, I love it (laughs)! I find satisfaction in the tediously slow manual production process. It brings me serenity. The fact that I am asked this very question again and again makes it all too clear to which extent we have devalued manual competence. Yes, cutting cardboard by hand may seem a bit outmoded in our technological age, but, apart from giving you complete control over your project from beginning to end, it also can feel more rewarding. It just feels good to be able to say I made this. My focus is on uniqueness and quality, not quantity. For me it is vital to alternate mental and physical processes, as the conceptualization and planning phase of an artwork can be equally exhausting.

But most importantly, making by hand allows me to explore thoughts that otherwise would remain unspoken. It fosters comprehension, or, to revisit a sentence I wrote at the very beginning of my artistic journey: I strongly believe that I wouldn’t be able to grasp the very essence of my work, if I didn’t sculpt it entirely by hand – just like landscape can be fully experienced only by walking.

Making by hand allows me to explore thoughts that otherwise would remain unspoken.